Today as I sit in front of my computer and think about the friends I have, the colleagues in the community and all of the community around my everyday life and realize just how many of us were born in a different country or are the children or grandchildren of those who left the Caribbean searching for a better life. Almost every person I know in my surroundings was from somewhere else, not necessarily another country but another city, another state…just somewhere else.

In that moment, I realized something: most of us are just one or two generations removed from being geographically located somewhere else. If we could travel back in time, not even that far, we would all be scattered across the islands, Jamaica, Trinidad, Barbados, Saint Lucia, Guyana, Grenada, or totally other Cities and States, living different lives, speaking in dialects full of rhythm, and wrapped in the warmth of our people, whoever they are.

Migration changes you. When we leave behind our home language, customs, and culture to settle in a new place, we inevitably leave a piece of ourselves behind. The transition forces us to adapt, to learn new words, customs, and even body language. Slowly, the “you” that left home becomes someone new.

Some adapt quickly; others never quite find their footing. But either way, the process transforms us. The island version or original version of ourselves begins to blend with the new environment, until we exist somewhere in between. As one of my adopted nieces, Nikki King, once said “I’m Guyanese-America, living on the hyphen”.

What is home, really? Is it the country or city where we were born? The house where we grew up? Is it where our family lives now, or does home travel with us, carried in memory and feeling?

For as long as I have lived, I thought of my true home as being Guyana, the country of my birth, the place where my roots ran deep. But there is an underlying fear or concern, that if or when I return after years in America, that I’ll realize that both home and I had changed. My memories, my imagination, my vision and even my accent had has changed. My habits will be different. People would say I had become “foreign.” Even the pace of life, the sound of the streets, and the rhythm of conversation would feel slightly offbeat to me.

I love my country deeply, but sometimes I feel or think that it has moved on without me. And though my memories remained rich and vivid, the Guyana I carry in my heart won’t quite be the same as the one I returned to.

I love my country deeply, but sometimes I feel or think that it has moved on without me. And though my memories remained rich and vivid, the Guyana I carry in my heart won’t quite be the same as the one I returned to.

Then there’s the other home, the place where we migrated. Maybe that’s New York, Toronto, London, or Miami. Those places taught us how to survive, how to work hard, how to build something from nothing. We learned to navigate snow instead of sunshine, and fast talk instead of small talk. We made friends, built families, and created a new kind of life.

But do we ever truly belong? This current political climate forces that question on us daily. For many of us, the answer is complicated. You can feel pride in where you are and still ache for where you came from. You can sound “too Caribbean” abroad and “too foreign” when you go home. That in-between space becomes our reality, a kind of permanent cultural limbo.

Time moves differently when you’re away. The village you left behind may no longer exist. Roads are widened, mango trees are cut down, the neighborhood aunties you once knew have passed on. The food tastes the same, yet somehow different. The place that raised you has evolved, just as you have.

When we return, it’s not to reclaim the past, but to reconcile with it. We go back to listen to the trees, listen to the birds and natural sounds of home, to feel the warmth of the breeze, and to remind ourselves that home is still part of who we are, even if we no longer fit perfectly within it.

Across the Caribbean, a quiet wave of remigration is underway. Professionals, retirees, and entrepreneurs from the diaspora are returning, not necessarily out of nostalgia, but with purpose. They’re building homes, starting businesses, volunteering, and investing in the lands that once nurtured their dreams.

This movement is about more than returning, it’s about renewal. It’s about redefining what home means for a new generation of Caribbean people who have lived abroad but never truly left in spirit.

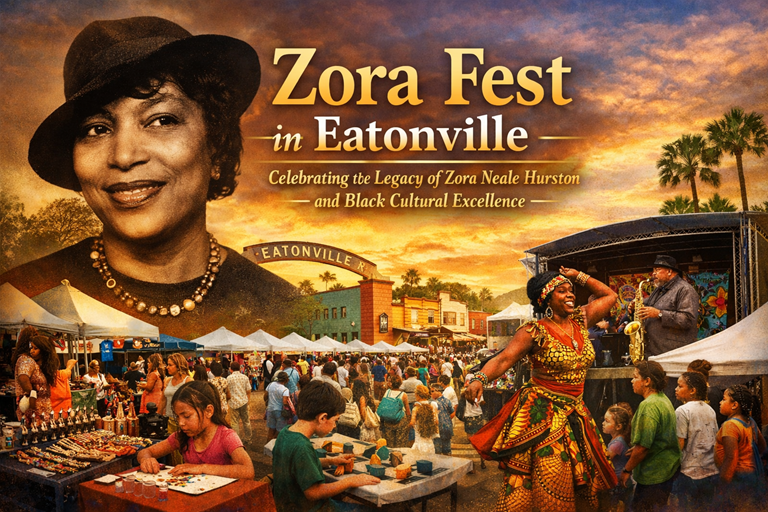

Perhaps the truth is that “home” isn’t one place. It’s wherever we find belonging, love, and purpose. It’s in the laughter of family and friends at a Sunday dinner, the smell of curry or jerk on the stove, the sound of a steelpan or reggae beat, and the warmth of community, whether in Georgetown, Kingston, Toronto, Port of Spain, or Brooklyn.

So maybe the goal isn’t to find where we belong, but to build belonging wherever we are. To connect instead of divide, to understand instead of “other.”

Because whether we left by choice, by necessity, or through the dreams of our ancestors, one truth remains constant for every Caribbean soul abroad:

There’s no place like home.